What Your Will Won’t Fix: The Hidden Investment Traps in Estate Planning

When I first sat down to draft my will, I thought I was future-proofing my family’s finances. But I quickly realized something no lawyer told me—your estate plan can crumble from within if your investment layout isn’t aligned. It’s not just about who gets what; it’s about what they actually receive after taxes, fees, and market shifts. I learned the hard way that poor asset placement can turn a well-meaning will into a financial headache. This is what I wish I’d known earlier. Too many people believe signing a legal document is enough to protect their legacy, but the truth is, without strategic investment coordination, even the most carefully worded will can fall short. The gap between intention and outcome often lies not in law, but in finance.

The Illusion of Safety: Why a Will Alone Isn’t Enough

A will is often seen as the cornerstone of estate planning, a final declaration of how one’s life’s work should be distributed. Yet, for all its legal authority, a will does not shield assets from financial erosion. It serves as a set of instructions, not a protective mechanism. Many families discover too late that the value passed down is far less than anticipated—not because of fraud or mismanagement, but due to overlooked financial dynamics. A will can name a beneficiary, but it cannot prevent tax burdens, avoid forced sales, or ensure that investments are positioned for long-term growth under new ownership.

The misconception arises from treating estate planning as a legal exercise rather than a financial one. Legal documents determine who receives assets, but investment strategy determines how much remains after costs. For example, an heir may inherit a portfolio worth $750,000 on paper, only to see its realizable value drop below $500,000 after taxes, penalties, and transaction fees. This gap is not the result of poor drafting—it stems from a failure to align investment accounts with the broader goals of wealth transfer. Without proactive planning, assets may be locked in high-tax vehicles, concentrated in illiquid holdings, or subject to market volatility at the worst possible time.

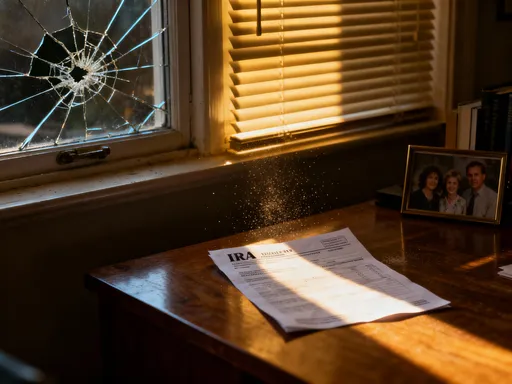

Furthermore, a will does not address liquidity needs. Final expenses, estate taxes, and administrative fees must be paid promptly, often in cash. If the bulk of an estate is tied up in real estate or retirement accounts, heirs may be forced to liquidate investments during market downturns just to cover basic costs. This not only diminishes the inheritance but can also disrupt long-term financial plans. The will may specify that a child receives a brokerage account, but if that account must be sold to pay debts, the intended benefit is lost. Therefore, estate planning must extend beyond document preparation to include a thorough review of investment structure, tax implications, and cash flow needs.

Another overlooked issue is family dynamics. A will can designate equal shares among children, but if one inherits a tax-deferred IRA while another receives a Roth IRA or taxable account, the actual value received may be far from equal. One sibling might face decades of tax liabilities, while the other enjoys tax-free growth. These imbalances can lead to resentment and conflict, undermining the very unity the estate plan was meant to preserve. Thus, the goal should not merely be legal compliance, but financial fairness and sustainability. A will is necessary, but it is not sufficient on its own.

Asset Location vs. Asset Allocation: A Critical Distinction

Most investors are familiar with asset allocation—the practice of dividing investments among stocks, bonds, and cash based on risk tolerance and time horizon. However, far fewer understand the importance of asset location, which refers to where those investments are held: in taxable accounts, tax-deferred accounts like traditional IRAs and 401(k)s, or tax-free accounts such as Roth IRAs. This distinction is not merely technical—it has profound implications for how much wealth is preserved and passed on to heirs.

Consider two retirees with identical portfolios: 60% stocks and 40% bonds. One holds all stocks in a taxable brokerage account and bonds in a traditional IRA. The other does the opposite, placing bonds in the taxable account and stocks in the IRA. Over time, the second investor is likely to leave more after-tax value to heirs. Why? Because bonds generate regular interest income, which is taxed annually in a taxable account. Stocks, especially growth-oriented ones, produce fewer taxable events until sold. By holding stocks in a tax-deferred account, the first investor triggers higher annual taxes, reducing the compounding effect. When passed to heirs, the brokerage account may have lower cost basis, leading to larger capital gains taxes upon sale.

The choice of asset location becomes even more critical in intergenerational planning. Traditional IRAs and 401(k)s are funded with pre-tax dollars, meaning every dollar withdrawn—by the original owner or the beneficiary—is subject to income tax. If such an account is left to a young heir in a high tax bracket, the tax burden can be substantial. In contrast, Roth IRAs, funded with after-tax dollars, allow tax-free growth and tax-free withdrawals. Placing appreciating assets in Roth accounts maximizes their long-term value for heirs. Yet, many investors fail to make this strategic decision, treating all accounts as interchangeable rather than optimizing them based on tax treatment.

Another common mistake is failing to consider required minimum distributions (RMDs). Starting at age 73, owners of traditional IRAs must begin withdrawing funds annually, regardless of need. These withdrawals increase taxable income and reduce the amount available for inheritance. By contrast, Roth IRAs have no RMDs during the owner’s lifetime, allowing assets to grow uninterrupted. A well-structured plan might involve converting some traditional IRA funds to Roth IRAs over time—a strategy known as Roth conversion—to reduce future tax liabilities and enhance legacy value. This requires careful planning, as conversions are taxable in the year they occur, but when done strategically, they can significantly benefit heirs.

The Tax Time Bomb: How Investment Accounts Trigger Unseen Liabilities

One of the most underappreciated risks in estate planning is the tax liability that can accompany certain investment accounts. To heirs, an inherited IRA or 401(k) may appear as a windfall, but it often comes with a hidden cost: income tax. Unlike assets held in taxable accounts, which receive a step-up in basis at death (meaning capital gains taxes are based on value at the time of inheritance, not original purchase price), tax-deferred accounts pass on the full tax burden. Every dollar withdrawn by the beneficiary is taxed as ordinary income, potentially pushing them into a higher tax bracket.

The impact can be staggering. Imagine a parent leaves a $500,000 traditional IRA to a child in the 24% tax bracket. If the child takes the entire amount in a lump sum, they could owe $120,000 in taxes. Even under the current rules, which allow most non-spouse beneficiaries to stretch distributions over ten years, the cumulative tax bill can still erode a significant portion of the inheritance. This is especially problematic if the heir is in their peak earning years and already subject to high marginal rates. What seems like a generous gift can quickly become a financial strain.

The situation is different with Roth IRAs and taxable brokerage accounts. Roth distributions are tax-free, provided certain conditions are met, making them ideal for wealth transfer. Brokerage accounts, while subject to capital gains tax upon sale, benefit from the step-up in basis, which eliminates taxes on appreciation that occurred during the owner’s lifetime. For example, if a stock was purchased for $10,000 and is worth $100,000 at the time of death, the heir’s cost basis becomes $100,000. If they sell it immediately, no capital gains tax is due. This feature makes taxable accounts highly efficient for passing on appreciated assets.

Yet, many estate plans fail to prioritize these distinctions. Investors often focus on maximizing account balances without considering the after-tax value to heirs. A portfolio heavily weighted in tax-deferred accounts may look impressive on paper, but much of its value could be lost to taxation. Strategic planning involves rebalancing not just asset classes, but account types. Shifting some investments from traditional IRAs to Roth accounts, or holding highly appreciated stocks in taxable accounts, can dramatically improve the net inheritance. The key is to view each account not just as a savings vehicle, but as a tool for tax-efficient wealth transfer.

Liquidity Gaps: When Assets Are Plentiful but Cash Is Scarce

It is possible to have a multimillion-dollar estate and still face a cash crisis at death. This paradox—being asset-rich but cash-poor—is a common yet preventable problem. Final expenses, funeral costs, legal fees, and estate taxes do not wait for markets to recover or properties to sell. If an estate lacks readily available funds, heirs may be forced to liquidate investments at inopportune times, such as during a market downturn or when holding long-term growth assets.

Real estate is a classic example. A home or rental property may constitute a large portion of an estate’s value, but converting it to cash takes time. Buyers must be found, inspections completed, and transactions closed—processes that can stretch over months. During that time, bills accumulate. If there is no liquid reserve, heirs may have no choice but to sell stocks or mutual funds, even if doing so means realizing losses or interrupting a long-term investment strategy. This not only reduces the estate’s value but can also create emotional stress during an already difficult period.

One effective solution is to maintain a dedicated liquidity reserve within the estate plan. This could be a separate savings account, a short-term bond fund, or a money market account earmarked for final expenses. The amount should be sufficient to cover estimated costs, typically ranging from $50,000 to $100,000 depending on the size of the estate and location. This buffer allows heirs to manage affairs without rushing into financial decisions. It also preserves the integrity of long-term investments, ensuring they are not sold prematurely.

Another strategic option is the use of life insurance. A permanent life insurance policy, such as whole or universal life, can provide a tax-free death benefit that serves as immediate liquidity. The proceeds can be used to pay debts, cover taxes, or support dependents, without touching investment accounts. When structured properly—such as placing the policy in an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT)—it can also reduce the taxable estate. While life insurance is sometimes viewed as a sales product, in the context of estate planning, it functions as a financial tool to bridge liquidity gaps and protect asset value.

Beneficiary Designations vs. Will Instructions: The Silent Conflict

One of the most surprising facts in estate planning is that beneficiary designations on financial accounts override the instructions in a will. This means that even if a will states that all assets should be divided equally among children, a retirement account with an outdated beneficiary form can send everything to an ex-spouse or a deceased relative. Because these accounts pass directly to named beneficiaries outside of probate, the terms of the will have no authority over them.

This conflict arises frequently and often goes unnoticed until it’s too late. People change jobs, remarry, or have falling-outs with family members, but they forget to update the forms on file with their brokerage or retirement plan administrator. A 401(k) opened decades ago may still list a former spouse as primary beneficiary. A custodial account for a child may not have been revised after a second marriage. In some cases, the named beneficiary has already passed away, causing the account to default to the estate—triggering probate and potentially higher taxes.

The consequences can be severe. Imagine a widow who remarries and updates her will to include her new spouse and stepchildren, but fails to change the beneficiary on her IRA. Upon her death, the IRA goes entirely to her children from her first marriage, bypassing her current spouse entirely. This not only contradicts her current wishes but can create financial hardship for the surviving spouse. Similarly, a parent who intends to treat all children equally may inadvertently favor one if only one is named on a significant account.

To prevent such outcomes, it is essential to conduct regular audits of all financial accounts. This includes retirement plans, IRAs, life insurance policies, bank accounts with payable-on-death (POD) designations, and brokerage accounts. The review should occur after any major life event—marriage, divorce, birth, death, or relocation. It should also be part of an annual financial checkup. By ensuring that beneficiary designations align with the overall estate plan, individuals can avoid unintended distributions and maintain control over their legacy.

Generational Investing: Aligning Portfolios with Long-Term Legacy Goals

Estate planning is not just about transferring wealth—it’s about transferring *sustainable* wealth. Investments intended to support future generations should be structured with the long-term in mind, not just the current owner’s retirement needs. This requires a shift in perspective: from personal financial security to intergenerational stewardship. A portfolio that is too conservative may fail to keep pace with inflation, while one that is too aggressive could expose young heirs to unnecessary risk.

One approach is to design portfolios that match the time horizon and risk tolerance of the next generation. For example, a grandchild who is 10 years old has a 60-year investment horizon. A portfolio held in a trust for their benefit should emphasize growth-oriented assets like equities, particularly low-cost index funds that provide broad market exposure with minimal fees. These investments can compound over decades, creating substantial wealth without requiring active management. In contrast, holding speculative stocks or high-fee active funds in a legacy account increases the risk of underperformance and erodes returns through expenses.

Tax efficiency remains crucial. Trusts used for wealth transfer are subject to different tax rules than individual accounts, often with compressed tax brackets. Placing high-dividend stocks or bond funds in a trust can trigger unnecessary taxes. Instead, growth stocks and tax-efficient funds are better suited. Additionally, minimizing turnover reduces capital gains realizations, preserving more value over time. The goal is not to chase returns, but to build a resilient, low-maintenance portfolio that grows steadily and predictably.

Gradual transitions can also support long-term success. Rather than transferring full control at a fixed age, some families use staggered distributions or advisory roles to help younger heirs develop financial literacy. This approach fosters responsibility and reduces the risk of impulsive decisions. By aligning investment strategy with educational and developmental goals, families can ensure that wealth not only survives but thrives across generations.

The Coordination Imperative: Bringing Lawyers, Advisors, and Investments Together

The most comprehensive estate plan can fail if its components are not aligned. Too often, attorneys draft wills and trusts in isolation, without consulting the client’s financial advisor. Meanwhile, investment professionals manage portfolios without full knowledge of the estate plan’s objectives. This siloed approach creates gaps where legal intent and financial reality diverge. A trust may be established to minimize taxes, but if the funding assets are poorly chosen, the tax benefits may be lost. A will may name equal beneficiaries, but if account types are not balanced, the distribution will not be equitable.

Integrated planning is the solution. It involves bringing together legal, tax, and financial professionals to review the entire picture. This collaborative process ensures that beneficiary designations match trust structures, that asset location supports tax efficiency, and that liquidity needs are met without disrupting long-term goals. For example, a financial advisor might recommend a Roth conversion to reduce future tax liabilities, while the attorney ensures the estate documents reflect this change. A CPA can model the tax implications of different distribution strategies, helping the family make informed decisions.

Regular coordination meetings should be part of the ongoing financial review. Life changes, tax laws evolve, and investment strategies adapt—so must the estate plan. An annual or biannual meeting with all advisors ensures that updates are communicated and contradictions are caught early. Technology can also help, with secure platforms allowing professionals to share documents and insights while maintaining privacy.

Ultimately, the goal is coherence. A will is important, but it is only one piece of a larger puzzle. When legal documents, investment accounts, tax strategies, and family intentions are fully aligned, the estate plan becomes more than a set of instructions—it becomes a legacy that endures. By recognizing that wealth transfer is as much a financial endeavor as a legal one, families can avoid common pitfalls and pass on not just assets, but security, stability, and peace of mind.